One of the most important factors in regulating our gut health, digestion and controlling our microbiome is the pH or acid level.

While often mentioned in terms of the stomach, the pH has a controlling role to play in the health of the entire GI tract from the mouth to the anus; changes in the “normal” pH anywhere in the gut can have major implications on the rest of the GI tract. The pH scale goes from 1, being very acidic, to 14, being very alkaline. The level in our blood and tissues should be constantly around 7.36, neutral, and the level in our GI tract varies from 1 to 8. We cover this a lot more in our book Overcoming Illness, which focuses on the role of inflammation, oxidation and acidosis in illness.

After initial breakdown by chewing, food is churned by the smooth muscles of the stomach and is broken down by hydrochloric acid and stomach juices (enzymes). The pH of the stomach is highly acidic, around 1.5 (1.0 to 2.5) due to the hydrochloric acid that helps to kill harmful micro-organisms, denature protein for digestion, and help create favourable conditions for the enzymes in the stomach juices, such as pepsinogen.[1] Not to mention sending messages along the GI tract that everything is working well in the stomach. If the pH is too high, say 3 or 4 (low acidity and more alkaline), then the system does not work and you end up with poor gut health, digestive and health complications. For example, premature infants have less acidic stomachs (pH more than 4) and as a result are susceptible to increased gut infections.[2] Similarly, the elderly show relatively low stomach acidity and a large number of people, more than 30%, over the age of 60 have very little or no hydrochloric acid in their stomachs.[3]

Similarly, in gastric bypass weight loss surgery, roughly 60% of the stomach is removed. A consequence of this procedure is an increase in gastric pH levels that range from 5.7 to 6.8 (not 1.5) making it more alkaline and, as a result, more likely to experience microbial overgrowth.[4] We see similar patterns in other clinical cases such as acid reflux in which treatment involves the use of proton-pump inhibitors[5] and celiac disease[6] where delayed gastric emptying is associated with reduced acidity and increased disease.

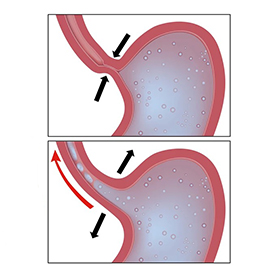

Unfortunately, acid reflux is often wrongly treated as a condition that involves the production of too much acid. It is, in fact, the stomach finding it difficult to digest the foods, most commonly as a result of not having enough acid to complete digestion. Medications (see my other posts) which further reduce stomach acid have serious and sometimes deadly side effects on health, the digestive process and the gut microbiota. Acid reflux affects about 20% of the adult population and is much higher in older people, which is consistent with studies showing lower stomach acid as we age.

[1] Adbi 1976; Martinsen et al., 2005.

[2] Carrion and Egan, 1990.

[3] Husebye et al., 1992.

[4] Machado et al., 2008.

[5] Amir et al., 2013.

[6] Usai et al., 1995.